Maria Sibylla Gräffin, née Merianin.

Starting a Career in Nuremberg?

by Margot Lölhöffel

Let us begin with a quotation about Maria Sibylla Merian taken from Natalie Zemon Davis, Women on the Margins (1995), p. 141:

“But she is a harder person to pin down [ …], since she left behind no autobiography, confessional letters, or artist’s self- portrait. Instead we must make use of the observing ‘I’ in her entomological texts and fill in the picture by attending to the people and places around her.”

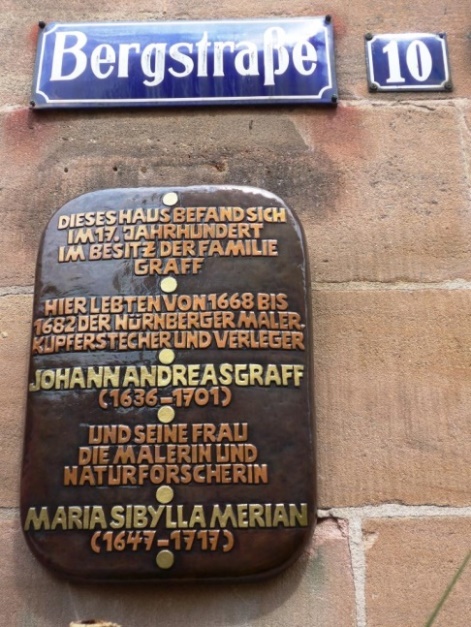

Merian’s House, her Portrait and her Garden

Davis recommends we take notice of the “places around her”: the family house in Nuremberg was the “House of the Golden Sun”, now Bergstraße 10, as the expert Karl Kohn discovered after painstaking research in the archives.* In 1668 Graff brought his young wife and their first baby daughter, Johanna Helena, from Frankfurt to his own house in his native town of Nuremberg. There, their second daughter, Dorothea Maria, was born in 1678 and they stayed there till 1682. Graff was from a family that enjoyed a good reputation, the son of a high-school headmaster, a poeta laureatus; and this spacious house in Nuremberg was an inheritance from his parents. It seems like a miracle that the house survived the almost complete destruction of this area in the Second World War.

Behind the bull’s eye windows in the upper storeys there was space for the caterpillars in wooden boxes. Maria Sibylla took great care in supplying them with greenery from their special host plants, collected in the gardens and landscape around her house. She observed their metamorphoses, drawing them and writing notes on the changes.

There are just a few portraits of Merian. The Fine Arts Museum Basel preserves a small oil portrait with a remarkable inscription on the reverse: “MARIA SIBYLA MERIAN AET SUAE 32. ANNO 1679”. This is no longer visible, since the canvas was stabilized by a wooden plate in 1935. The intriguing painting is not signed, but in 1678-1679 Jacob Marrell came to Nuremberg and stayed in the house of his former apprentice, Johann Andreas Graff, for several months. Therefore we assume that he was the one who painted his stepdaughter.

Comparing this portrait with her portrait as an old lady in Amsterdam in the Dutch edition of Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung (Caterpillar book) of 1717 in the Artis Library in Amsterdam, it is astonishing how similar the shape of her head and her facial features are despite the fact that at least thirty-five years had passed between the two portraits. This supports the conclusion that the image of the younger lady is an authentic portrait of Maria Sibylla.

If you allow for the aging process and probable loss of teeth (which changes the volume and shape around the mouth rather a lot) these portraits appear to be of the same person, as the nose, eye and mouth shape are very similar in both. (Animation: © Theo Noll, Nuremberg)

Jacob Marrell (attribution), Portrait of Maria Sibylla Merian, 1679,

Kunstmuseum, Basel. Oil on canvas, 59 x 50,5 cm (photo by Martin P. Buehler).

Jacob Houbraken after Georg Gsell, Portrait of Maria Sibylla Merian.

Engraved title page from: M.S. Merian, Der rupsen begin, voedzel

en wonderbaare verandering … Amsterdam 1717. Coloured counterproof.

Amsterdam, Artis Library, University of Amsterdam.

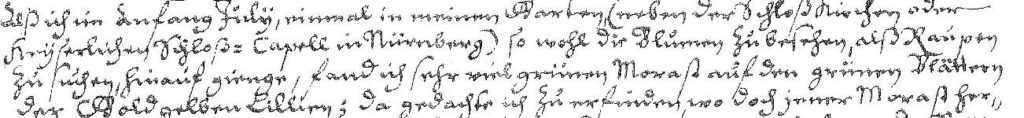

The family house and the portrait of 1679 belong to the legacy of her time in Nuremberg. Furthermore, there is an authentic place where Maria Sibylla spent many hours during her Nuremberg period. From her personal Studienbuch (Book of Studies) in St. Petersburg we know about her garden in Nuremberg:

“For when I walked up to my garden in early July (next to the Castle Church or the Imperial Chapel in Nuremberg), both to look at the flowers and to find caterpillars, I found a lot of green mud on the green leaves of said lilies […].”

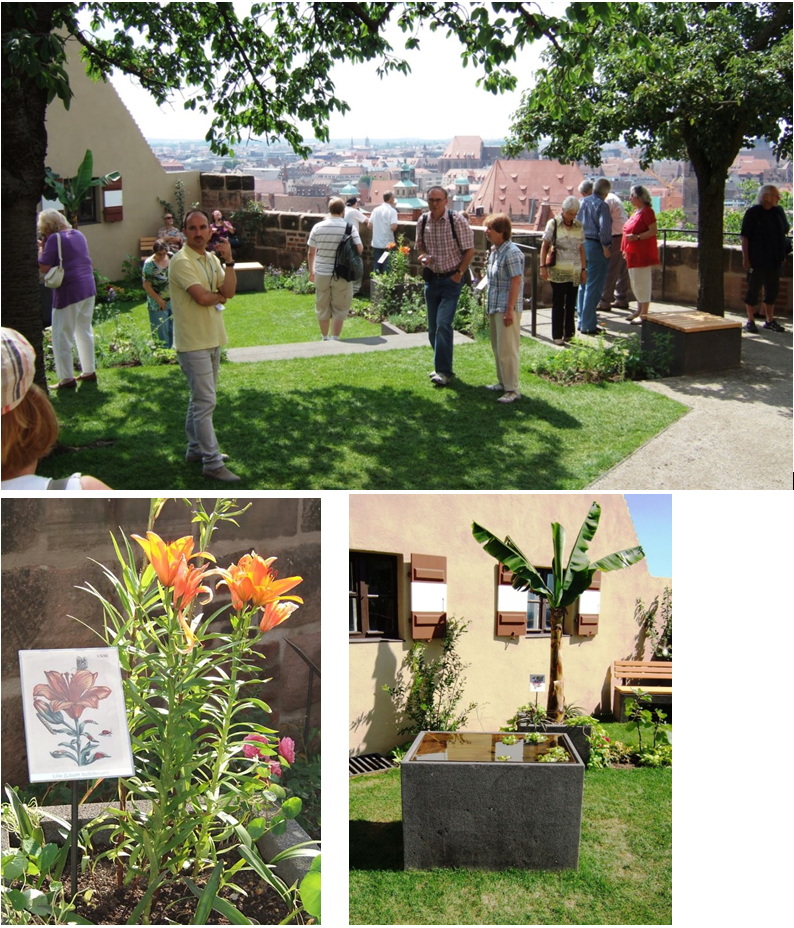

The garden next to the Castle Chapel is small. There remains a two-storey garden house that already existed in Maria Sibylla’s time and suffered only slight damage in the Second World War. In 2013, the garden was dedicated to Maria Sibylla Merian and showcases exclusively plants that are depicted in her books. The flower beds have been arranged diagonally, pointing to the landscape beyond Nuremberg and to distant regions, reminding us that Maria Sibylla started out from Nuremberg and travelled to Wieuwerd, Amsterdam and Surinam.

This garden is a wonderful, living, green and blossoming paradise where we can treasure her memory. It is a monument in the form of landscape art, one which may be more suitable than a Merian statue. This delicate garden needs a great deal of care. Therefore it is open to the public only on Sunday and Monday afternoons from April to October. Despite these restricted opening hours, more than 100,000 visitors a year come to visit it free of charge.

Places around her: hundreds of gardens, the pride of their owners

Nuremberg had been a city of gardens from medieval times onwards. With a growing population and denser building within the city, many gardens were relocated outside the city walls in the protected area of the outer defence ring. This is where not only the rich patrician families, but also civil servants, medical doctors, lawyers, craftsmen and publicans created their own little corners of paradise outside the city, which in summer was stuffy and foul-smelling. Indeed, experts calculate a total of at least 400 gardens for Merian’s time in Nuremberg. Maria Sibylla was permitted to observe fauna and flora in quite a few of them; and in her Studienbuch (Book of Studies) we find notes on where she collected her finds.

How could Maria Sibylla come to have such a garden at her disposal? This question brings us to “the people around her”: the great uncle of Maria Sibylla’s pupil Clara Regina Imhoff was Treasurer of the City Council, Imperial Sheriff and Keeper of the Castle. His realm comprised several gardens; therefore, he could relinquish the small garden next to the chapel.

A Woman in a City of Art and Sciences

Nuremberg recovered quickly after the Thirty Years’ War and became an attractive destination for highly qualified, specialist immigrants, who often settled there for good. Thus, in 1662 the engraver Jakob von Sandrart was able to establish the then innovative Painters’ Academy. His famous uncle, Joachim von Sandrart, one of the first biographers of Maria Sibylla, settled permanently in Nuremberg. One of the directors of the Painters’ Academy, the painter Johann Paul Auer, gave lessons to her.

In Altdorf, a fortified rural town on Nuremberg territory, a university prospered with famous academic teachers in Philosophy and Natural Sciences (the latter as part of the study of Medicine). However, scientific institutions, such as an observatory situated on a bastion of the castle and a huge Council Library, were also open to the public in central Nuremberg.

In Lutheran Nuremberg, it was not unusual for women to work as painters, embroiderers or teachers of girls. Idleness was considered a vice and even girls in the upper strata of society had to learn something useful. Maria Sibylla’s Jungfern Combannÿ (Company of Maidens) included girls from the Council families, such as Clara Regina Imhoff, as well as from the middle classes which worked in arts and crafts, such as a daughter of the art dealer and publisher Paul Fuerst.

People around Maria Sibylla: educated citizens with private book and art collections and an interest in the natural sciences

Unlike in other cities, in Nuremberg Merian’s interest in caterpillars was not considered “sinful”, for caterpillars were by no means despised as Teufelsgewürm (Devil’s worms). Dissected butterflies were an attractive part of private collections in cabinets of curiosities (Wunderkammern). Science and reverence for God’s wonderful creation, including the smallest and most insignificant creatures, corresponded closely to the attitude to life in Nuremberg urban society.

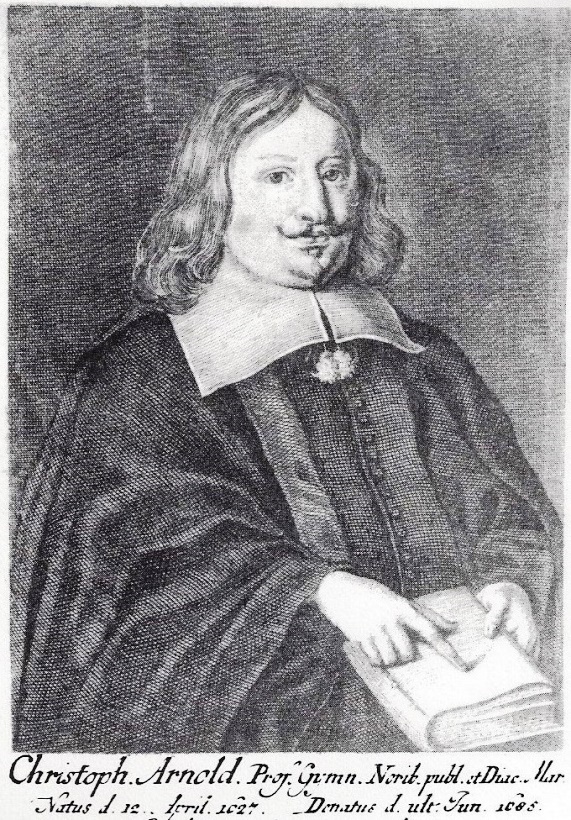

Thus in Nuremberg Maria Sibylla did not have to fear being prosecuted for her research into insects. On the contrary, her work was supported. Let us take Christoph Arnold as an example of the “people around her”. He was a teacher at the Egidien Grammar School, Dean at the Church of Our Lady and one of the first members of the “Pegnesischer Blumenorden”, a famous society for the promotion and improvement of the standard of German which still exists to this day. In Maria Sibylla’s first volume of Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung (1679), directly after the title etching and title page, we find a poem by Christoph Arnold. There he places the female author on a par with the most famous insect researchers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries who had published before Maria Sibylla. Right at the beginning of the poem Arnold confirms:

„Es ist verwundernswert,

dass ihnen auch die Frauen

dasjenige getrauen

zu schreiben mit Bedacht.

was der Gelehrten Schaar

so viel zu thun gemacht. …

Jedoch ist lobenswert,

daß ihnen eine Frau es gleich

zu thun begehrt …

daß ein kunstreiches Weib

dies alles selbst geleist

zu ihrer Zeitvertreib.“

“It is cause for astonishment / that women, too,

trust themselves to write / judiciously /

on what has occupied the hordes of scholars so much.”

With his central statement he stamps the seal of approval on Merian’s work:

“But it is laudable / that a woman strives

to emulate their [the male researchers’] deeds. […]

that an ingenious woman

achieved all this / to while away her time.”

Arnold not only knew their names, but actually kept several of these English, Dutch, Italian and Spanish works in his private library. His collection comprised about 9,500 printed works; and this was only one of about seventy private libraries in Nuremberg at that time. Doubtlessly, Maria Sibylla was familiar with such bibliographical treasures and took a close look at the pages with illustrations of insects and spiders.

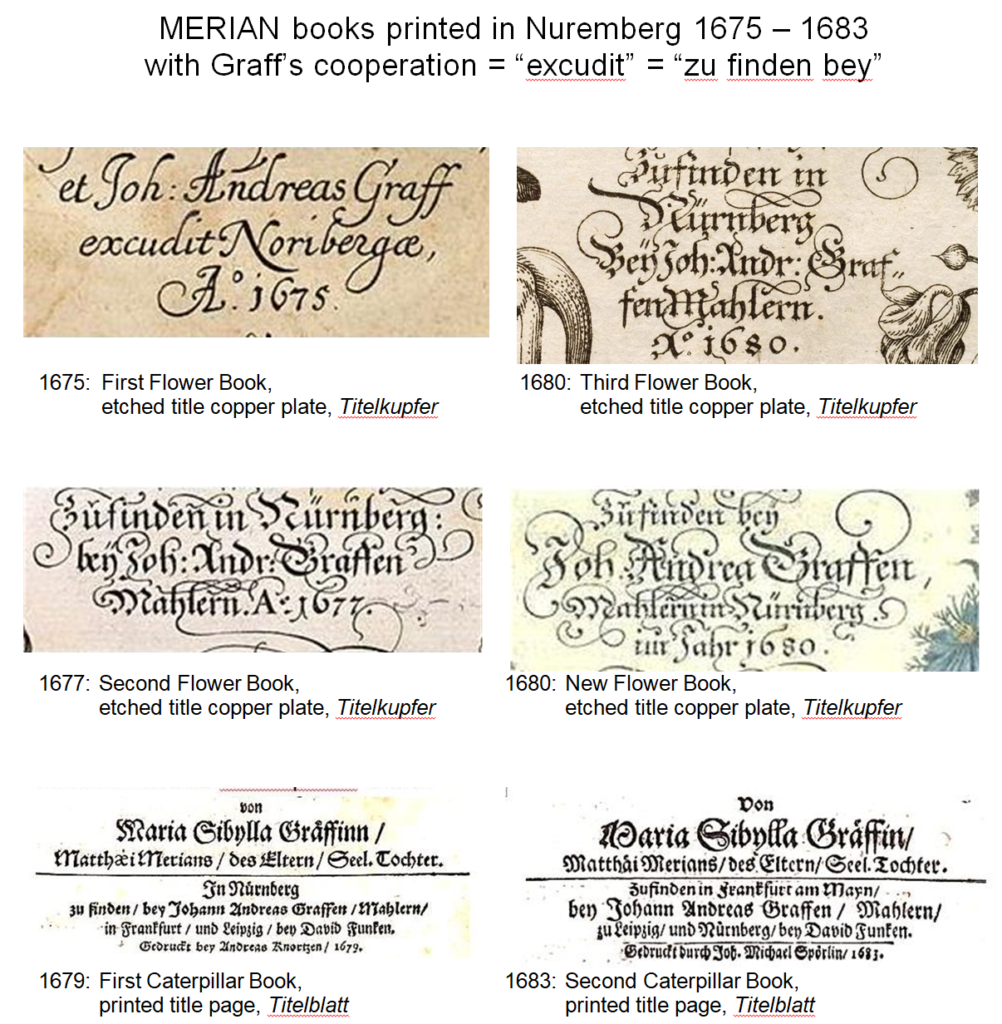

Johann Andreas Graff, companion and supporter of his wife

During the fourteen years when Merian lived in Nuremberg three series of her copperplate prints in the Blumenbücher (Flower Books) were published in 1675, 1677 and 1680. In a second edition (1680) they were combined into one, the Neues Blumenbuch (New Flower Book). The first part of Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung (Caterpillar Book) had already appeared on the market the previous year (1679). The second part had been printed in Nuremberg by the time the Graff-Merian family returned to Frankfurt because Merian’s stepfather Jacob Marrell had died. For all sixth above-mentioned works, Merian’s husband Johann Andreas Graff acted as her publisher and as the responsible representative vis-à-vis the authorities in Nuremberg and to business partners. After that, however, twenty-two years had to pass before Maria Sibylla could publish a new book, her Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium.

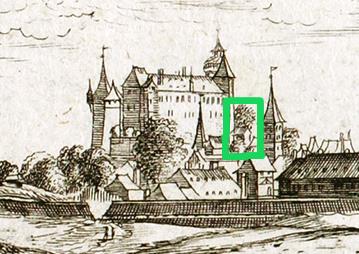

Hence it is indispensable to mention him as another important “person around her”. His own skills as a painter and copperplate etcher were well regarded in the city. Here one example must suffice: Poetenwäldlein gegen Nürnberg (Poets’ Grove looking towards Nuremberg) in the valley of the River Pegnitz, with Nuremberg Castle on the horizon.

The signature on the bottom left, “JAGraff del.” = delineavit, confirms that Graff made the original drawing: he made the design, the perspective and all the details. On the right you see a second signature: “JUKraus sc:” = sculpsit. Johann Ulrich Kraus was a famous etcher with a workshop in Augsburg. On this small-format view (about 12 to 17 cm) everything is so precise that one can even detect the garden house of the Graff-Merian-family as part of the Castle. In many museum inventories the prints based on Graff’s design can only be found listed as works by Kraus. Thus even in Nuremberg Graff was almost forgotten.

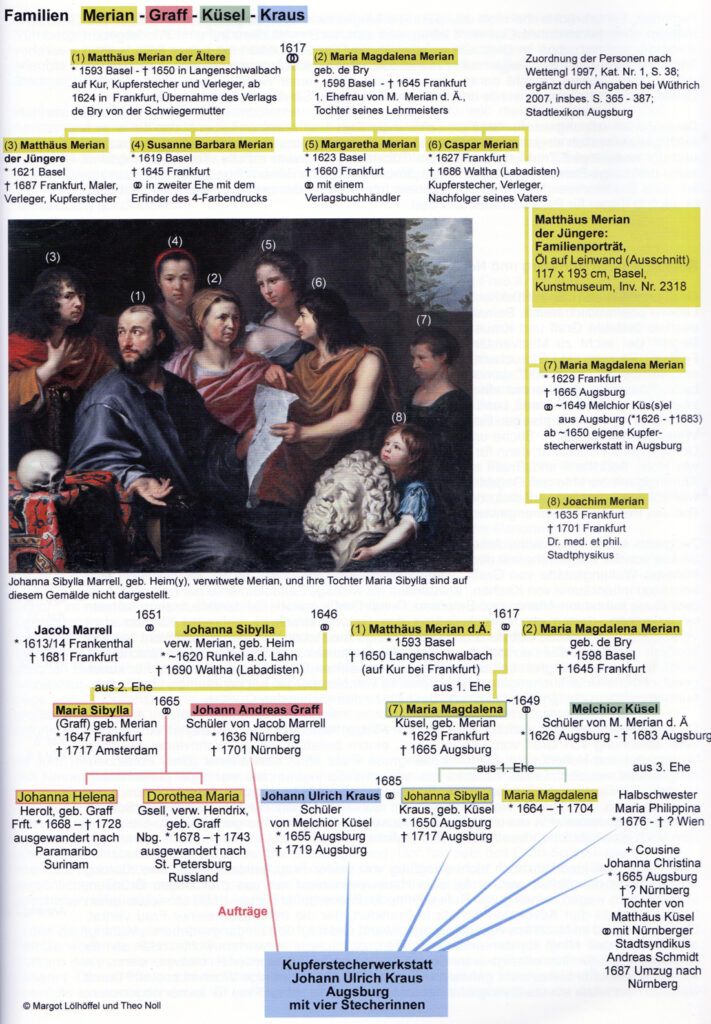

The question of why Graff cooperated with Kraus brings us back to the Merian family and illustrates the importance of family connections at that time. The family lines are too complicated to explain in detail, but at first glance one can imagine how difficult it was to trace and document such relationships. The most important facts in our context are the following: J. U. Kraus’ father-in-law, Melchior Küsel, had been an apprentice of Matthäus Merian the Elder (1). His wife Maria Magdalena (7) was one of M. Merian’s daughters (half-sister to Maria Sibylla). Their daughter Johanna Sibylla was an excellent etcher and head of the etching and print shop in Augsburg after her father’s death until she married J. U. Kraus at the age of thirty.

the catalogue of the exhibition on Graff mentioned below (p. 45).

Johann Andreas Graff had given up his own etching and copperplate-printing workshop when he followed his family to Frankfurt after Jacob Marrell, Maria Sibylla’s stepfather, had died in 1681. In 1686 he followed his family , including his mother-in-law, from Frankfurt to the Labadist religious community on the Waltha estate in Wieuwerd, where he was not accepted. Thus, for his last fifteen years the excellent Kraus workshop in Augsburg was the best solution for transforming his drawings into etchings designed to present his work to customers and to earn money.

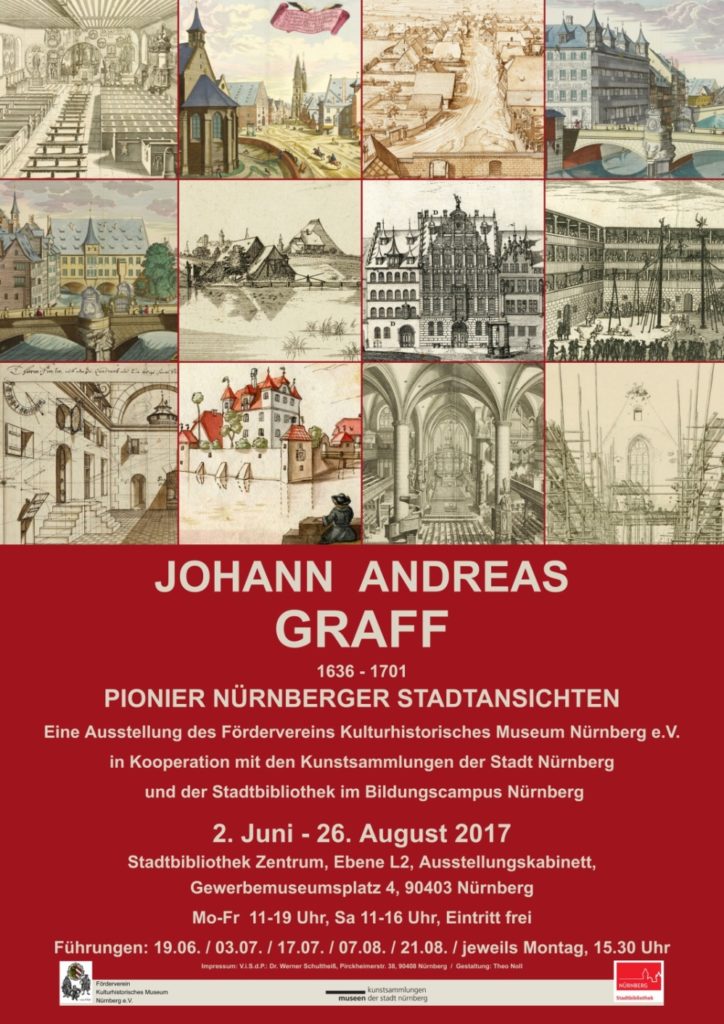

Projects to commemorate Merian and Graff

On June 2nd, 2017 an exhibition was opened in the City Library of Nuremberg that ran for three months – probably the first one ever dedicated to Graff. The catalogue of this exhibition contains a list of his works and additional material found in archives: for example, the family tree shown above and the detailed map of the territory of the Labadist community in Waltha, where Maria Sibylla Merian lived for about five years. In the past two years, since 2017, nearly all the 1,000 copies of the catalogue were sold or given free of charge to institutions (public libraries, museums, archives and specialists in Merian research).

However, part of this catalogue has formed the basis for a new virtual presentation on the portal of Google Arts & Culture from June 2019 onwards: There, Graff’s work is on show in two virtual exhibitions. You can find more information about these and the appropriate links on the home pages of the present website.

Re-evaluating Merian and Graff

Cooperation and networking were decisive in the seventeenth century. Only with Graff’s help and consent could Merian work successfully in Nuremberg as a draftswoman, painter, embroiderer, copperplate etcher, taxidermist, author of non-fiction books, and as observer of and teacher on nature. In later periods in her life she even became more independent as a businesswoman.

It is to be hoped that the stereotypes of Merian’s inept husband, of the supposedly limited possibilities for women to work (an alleged ban on painting in oils) and of an alleged threat to her life from – entirely fictional – witch trials will be shelved once and for all. On the contrary, with the virtual exhibitions of Graff’s work on the portal of Google Arts & Culture, people across the globe can form a more vivid and authentic impression of Nuremberg, the city where Merian lived for fourteen important years of her life.

This is intended to contribute to a “pool of information” open to all Merian researchers in the future. Furthermore, it would be desirable to establish a working group which compared the economic, social and cultural structures in Frankfurt, Nuremberg, Amsterdam and Surinam. Such comparison would help to elaborate a “frame” by explaining the important preconditions and opportunities for Merian’s own extraordinary metamorphosis. However, it should not attempt to “pin Maria Sibylla down” like a butterfly, as Davis already warns us against such an impossible undertaking.

Approaching the future

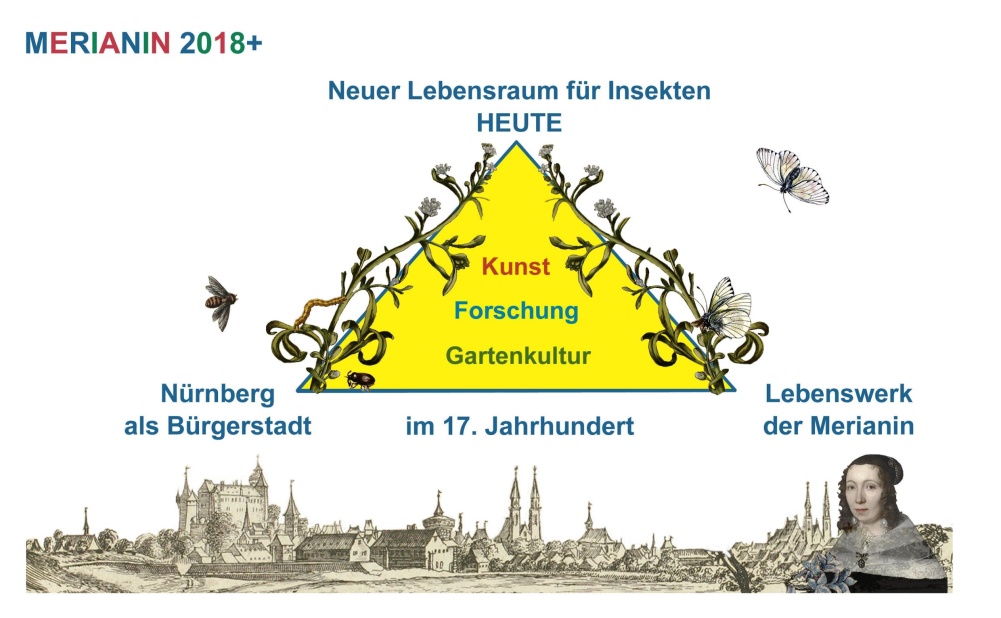

In 2018, 350 years after Maria Sibylla Merian had come to Nuremberg, we celebrated our own local jubilee year with some new initiatives under the slogan: “MERIANIN 2018+. New Habitats for Insects”. Since then we have distributed our own brochure comparing Merian’s research with the needs of bees, bugs and butterflies nowadays.

We have developed some ideas for transforming public parks, private gardens and even balconies into small corners of Paradise for insects. We go into schools with caterpillars and the appropriate equipment. Children observe their metamorphosis and – after some weeks ‒ take the butterflies to the nearest habitat meadow to release them.

Our very active Children’s Museum offers several programs and project days, which combine the urgent need to protect our environment with Merian’s exemplary work. Together we have produced three large roll-ups about (1) Merian’s life and work, juxtaposed with (2) similar information on Johann Andreas Graff and (3) facts about and illustrations of Nuremberg in the period during which they lived there. We offer them for public events in garden centers or even at the Botanical Garden in Erlangen. These are only some examples of the multifaceted activities under the virtual patronage of Maria Sibylla Merian.

She is becoming increasingly popular in Nuremberg. Many of the people who live here already know that she was “Frau Gräffin” [Mrs Graff] in her Nuremberg time, but prefer to call her “Merianin”, with the feminine ending on her maiden name usual for the time. People of very different social and professional levels (not only naturalists or art historians) are interested in knowing more about her and about their own city in the second half of the seventeenth century, a period that has been neglected up to now in scholarly research – as have Graff and his merits.

In the last two years it has become obvious that people are more attentive towards and cooperative in fighting for new solutions to the problems of our time when they find echoes in their local history and can be proud of their own city’s past. So, we hope that our success will go on, deeply ingrained in our own tradition.

* Sources in archives, museums and libraries proving the facts mentioned in this presentation can be found in the endnotes of:

‘Maria Sibylla Merianin and Johann Andreas Graff – Gemeinsames und Trennendes’, in: Nürnberger Altstadtberichte, 40 (2015), 37-76; 41 (2016), 64-116; 42 (2017), 40-87.

Johann Andreas Graff – Pionier Nürnberger Stadtansichten, exhibition catalogue with list of his works, essays and archive material, Nürnberg 2017, ISBN 978-3-00-056458-1.